Disney has been cranking out live action remakes of its animated classics for the past few years — in fact, Guy Ritchie’s take on “Aladdin” is currently at the top of the box office.

But these distinctions get tricky with the growing reliance on computer generated visual effects. “The Jungle Book,” for example, mostly features a single live actor interacting with CGI animals. And “The Lion King” (scheduled for release on July 19) takes that approach even further: Everything you seen onscreen has been created on a computer.

I got a chance to visit the “Lion King” set in December 2017, where I participated in a group interview with Jon Favreau, who directed both “The Jungle Book” and this new film. When asked whether he considers this a live action or animated movie, he said, “It’s difficult, because it’s neither, really.”

“There’s no real animals and there’s no real cameras and there’s not even any performance that’s being captured,” Favreau acknowledged. “There’s underlying [performance] data that’s real, but everything is coming through the hands of artists.”

At the same time, he argued that it would be “misleading” to call this an animated film. For one thing, the visuals aren’t stylized in the way you’d expect in a cartoon. Instead, the aim was to create animals that look even more realistic than the ones in “The Jungle Book” — Favreau said the footage should feel like “a BBC documentary,” albeit one where the animals talk and sing.

“Between the quality of the rendering and the techniques we’re using, it starts to hopefully feel like you’re watching something that’s not a visual effects production, but something where you’re just looking into a world that’s very realistic,” he continued. “And emotionally, feels as realistic as if you’re watching live creatures. And that’s kind of the trick here, because I don’t think anybody wants to see another animated ‘Lion King,’ because it still holds up really, really well.”

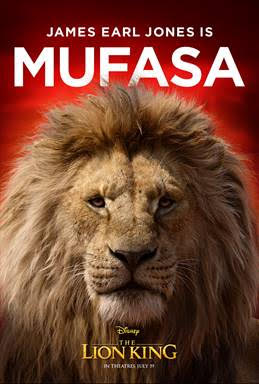

To achieve this, Favreau said he wanted this to have “the feeling of a live action shoot,” including the way he shot with the actors (Donald Glover plays Simba, Beyoncé plays Nala and James Earl Jones returns as Mufasa). Given the goal of creating realistic animals, Favreau said the traditional motion capture approach didn’t make sense, but he still wanted the actors to “overlap and perform together and improvise and do whatever we want.”

So he brought them to a soundproofed stage, and they performed “standing up, almost like you would in a motion capture stage — except no tracking markers, no data, no metadata’s being recorded, it’s only long-lens video cameras to get their faces and performances.”

Favreau compared this to shooting with Robert Downey Jr. and Gwyneth Paltrow on the original “Iron Man,” where he “tried to have multiple cameras and let Gwyneth and Robert improv when I could, because there’s so much of the movie you can’t change, because it’s visual effects.”

And even when he wasn’t working with actors, Favreau still “shot” the scenes with live action cinematographer Caleb Deschanel. That meant building a virtual world using the Unity game engine, then adding the digital equivalent of real-world production elements like lights and dolly tracks to block and film seen in that world. The filmmakers could use iPads to add, move and eliminate those elements, and could put on Vive VR headsets to explore the world.

“That’s the way I learned how to direct,” Favreau said. “It wasn’t sitting, looking over somebody’s shoulder [on a] computer. It was being in a real location. There’s something about being in a real 3D environment that makes it — I don’t know, just the parts of my brain are firing that fire on a real movie.”

To be clear, those virtual scenes aren’t what you’ll actually seen onscreen. Instead, they provide guidance for the animators to create far more detailed shots. Favreau said that in a sense, he was trying to resist the complete freedom that the computer generated approach can bring.

“I find that what the flexibility of digital production has done is given the opportunity for people to postpone being decisive,” he said. “It used to be if, you know, you built a big animatronic dinosaur, you had to make sure you got that shot right and framed right and it worked … And so, part of this experiment is to see if we really lock in early, as animated films do, and spend all of our time refining.”

As for why he’s going through all this effort to remake a film that, by his own admission, holds up really well, Favreau said he was inspired by the success of the stage play: “People will go see the stage show, and they’ll also see the movie, and you could love both of them and see them as two different things.” Similarly, he said his team set out to “create something that feels like a completely different medium than either of those two.”

Comments

Post a Comment